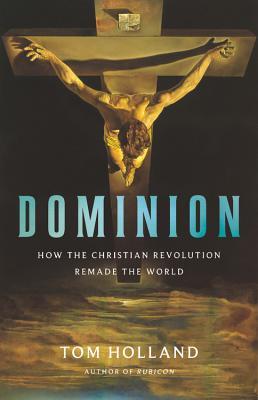

Dominion is a challenging read. Not only because of its hefty page count and sweeping coverage of over two thousand years of history, but because it offers a fascinating lens through which to trace the development of the Western mind, right up to the present day. In Dominion, Holland’s core thesis is that the norms, values, and practices of the Western world have been built upon the immovable foundation of Christianity. Across the better part of 600 pages, Holland takes the reader on a journey across time from antiquity through the mid-2010s, pointing out how, as he sees it, concepts as wide-ranging as universal human rights, science, sexuality, abolitionism, feminism, communism, fascism, secularism, and even religion itself are inherently defined through a uniquely Christian lens. It makes for a compelling pitch, and I picked up Dominion after hearing Holland discuss many of these topics on the excellent podcast he co-hosts, The Rest is History.

Overall, I enjoyed Dominion. Holland is clearly passionate about his thesis and is an excellent researcher. And on the whole, I agree with his thesis more than I don’t. As a student of human rights law and history, I am very aware of the extent to which the assumptions of human rights field and the post-war international order are being challenged by the rising influence of China, India, and other non-Western powers. And as someone who is fascinated by both historical and contemporary political and social justice movements, I have long found it ironic that the most secular and atheistic among us (whether they be sincere communists, “Invisible Hand” capitalists, or “woke” leftists) are as skilled at evangelizing, rooting out heretics, and elevating martyrdom as the “superstitions” and “backward” Christians they often denounce and dismiss. Dominion does an excellent job articulating these fundamental ironies that exist within all of us who count ourselves among the descendants of Western culture.

There are times, however, where I think Holland’s argument requires squinting just a little too hard to seem credible, and one of this book’s flaws is that it at times relies on anecdotes to make too sweeping a claim. The other flaw is that this book is too long. In the preface, Holland denies that his ambition is to write a history of Christianity, but the first two-thirds of Dominion read like one. While I understand the necessity of laying the groundwork in establishing figures like Paul, Augustine, Gregory VII, and Luther (just to name a few) and their essential theological contributions, there are times where Holland’s clear fascination with the Roman world and the Medieval Church in particular lead to a level of detail that is likely to exhaust or repel more casual readers who came to this book hoping for more on Christianity’s relevance to our world today. The chunky paragraphs and Holland’s writing style don’t help. I have heard Holland himself say before in an interview that Dominion is too long, and hopefully, his diagnosis of his own work could have been streamlined is similar to my own.

All in all, Dominion was a very good read and a worthy challenge for anyone willing to think deeply about themselves and the society in which they live as heirs of an ancient lineage riddled with as many continuities as contradictions.