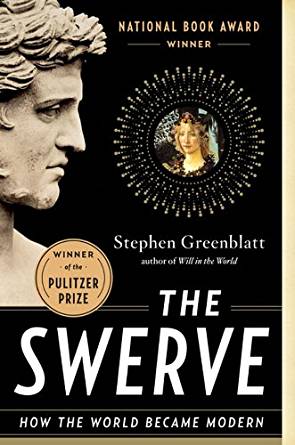

In its subtitle, Stephen Greenblat’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern promises to explain a whole lot in under three hundred pages. And somehow, through the narrative device of tracking the rediscovery of Lucretius’s poem On The Nature of Things in the 15th century, Greenblat makes a compelling case that this poem, plucked from obscurity by bibliophile Poggio Bracciolini, embodied the pivoting of the European mind from the medieval to the renaissance. Greenblatt is careful not to overemphasize the influence of this one text in the transformation of the West, and yet, by the time I finished this book, I began to wonder whether he had in fact understated its influence.

In short, Lucretius’s On The Nature of Things is a poetic amalgamation of the Epicurean school of philosophy, which, in contrast to the conservative dogma of Christendom or pagan Stoicism, emphasized the natural and rational over the spiritual and metaphysical. The Epicureans, as Greenblatt explains, were permissive of pleasure and liberation because of their underlying belief that this mortal life is all there is. We are all beings made of atoms that swerve together and pull apart in an endless cycle for all time. Rather than submitting to nihilism, the Epicurean approach argues for a richer, fuller embrace of life’s offerings and gifts: pleasure, exploration, sexuality, discovery, individual expression, art, science. A full explanation of these tenets can be found in chapter eight.

It is not hard to see the connections between the ideas Lucretius expresses in On the Nature of Things and the emerging wonders of the renaissance world. Across the book, and predominantly told through the story of Poggio Bracciolini, Greenblatt surveys the dark age decay of Greco-Roman literate society; the orthodoxy that dominated the medieval church, its monasteries, and its curia in Rome; the difficulty with which ancient texts were preserved, and the unlikelihood of their survival across the millennium between the sacking of Rome and Poggio’s rediscovery; and the profound impact Lucretius’s ideas had on giants of the modern world, including Galileo, Shakespeare, Newton, More, Luther, the Medicis, and Jefferson.

For a relatively short book, The Swerve at times veered into being repetitive and unwieldy in its structure. There are a lot of names, events, and ideas name dropped here that can feel overbearing, especially to readers without existing knowledge. But ultimately, the story Greenblatt tells in The Swerve is a fascinating and important one, while also giving readers a taste of differing ways of thinking about the universe, culture, and the human experience.