“The life of a child buried alive while digging for cobalt counted for nothing. All the dead here counted for nothing. The loot is all.”

“Were women and girls being slowly poisoned in toxic water as they rinsed the stones? Were boys losing legs in pit wall collapses? Were children inhaling toxic particulates as they hacked at the dirt? Were people being paid anything akin to a decent wage? Were children being shot? No one asked, no one cared — not even in the largest copper-cobalt buying market in the DRC.”

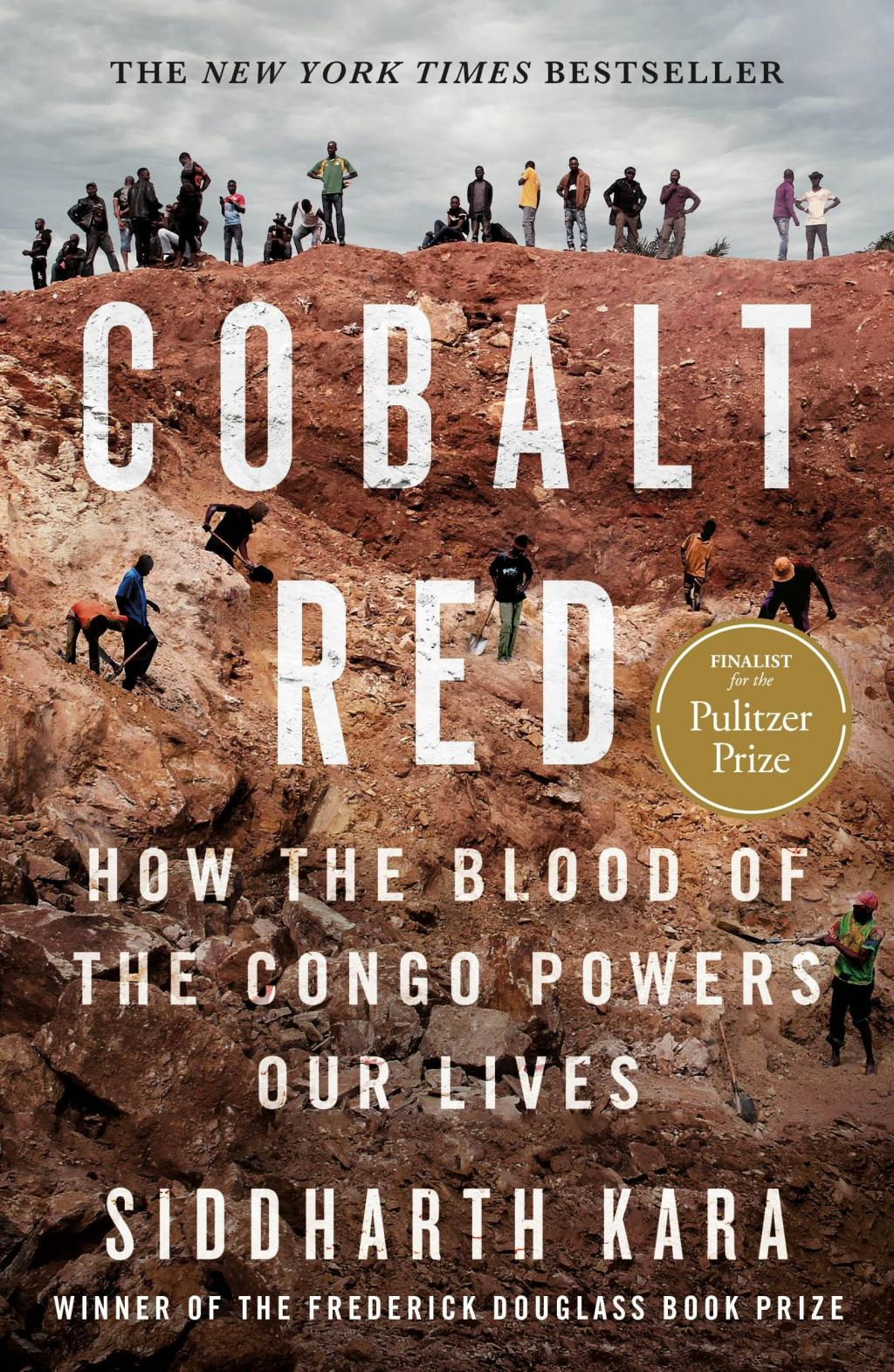

Cobalt Red is a serviceable book that carries some of the most important, damning, heartbreaking, infuriating, and frustrating messages and stories one can read about contemporary human-rights atrocities in the Congo. I am deeply appreciative of Siddharth Kara for traveling to the Congo, witnessing the horrors he did, and relaying the firsthand accounts of the victims, agents, and perpetrators of this nefarious vortex of suffering. As Kara argues, one of the best ways to bring attention to injustices is to amplify the voices of those directly impacted. The book is packed full of horror stories, saddening tragedies, and deeply upsetting retellings of workers being buried alive, children left crippled and cursed to live with chronic pain, and violent retaliation against those who fail to deliver their silence and obedience to a system that gives no care to broken bodies or hearts.

Kara does not shy away from implicating real people and corporations in their culpability and complicity in modern-day slavery, child labor, and environmental degradation on full display in the Congo. Multinational corporations relying on cobalt for everyday products (Apple, Samsung, Tesla), the Chinese government and its state enterprises, and shady actors from Belgium, Lebanon, and even the Congo itself are all called out unflinchingly. The contents of Cobalt Red are uncomfortable to read. And they should be. How does it make sense that, in the twenty-first century, people are expected to survive on barely a dollar a day? How is it that children have their dreams and limbs torn from them while the system doesn’t bat an eye? How is it that the physical source of global wealth and economic growth in the digital age is home to some of the worst abuses and deprivations on the planet? None of it makes sense. Nor should it.

As worthwhile a read as Cobalt Red is for the spotlight it shines on the historical and contemporary plights of the Congo and its people, it is unhelpfully laborious to read at times. Rather than following a narrative or thematic structure, the entire book unfolds as a series of location-based scenes, each a jumbled mix of human stories and acronym-heavy business and mining jargon. Unless you are particularly interested in the different types of cobalt mines and mining techniques, much of this will likely go over your head and add little to the heart of the book.

Similarly, the book does not do much to situate the reader. There is a chapter dedicated to Congo’s history (which, for some reason, appears in the middle of the book rather than at the beginning), but it is quite short. There is also a frustrating lack of visual aids such as images and maps. Luckily, having previously read Tim Butcher’s incredible Blood River, this was less of a problem for me personally. The reporting in Cobalt Red is so essential that it is a shame its impact is somewhat dulled by its presentation. At times, the book reads more like congressional testimony than an effort to raise broad public awareness and outrage.